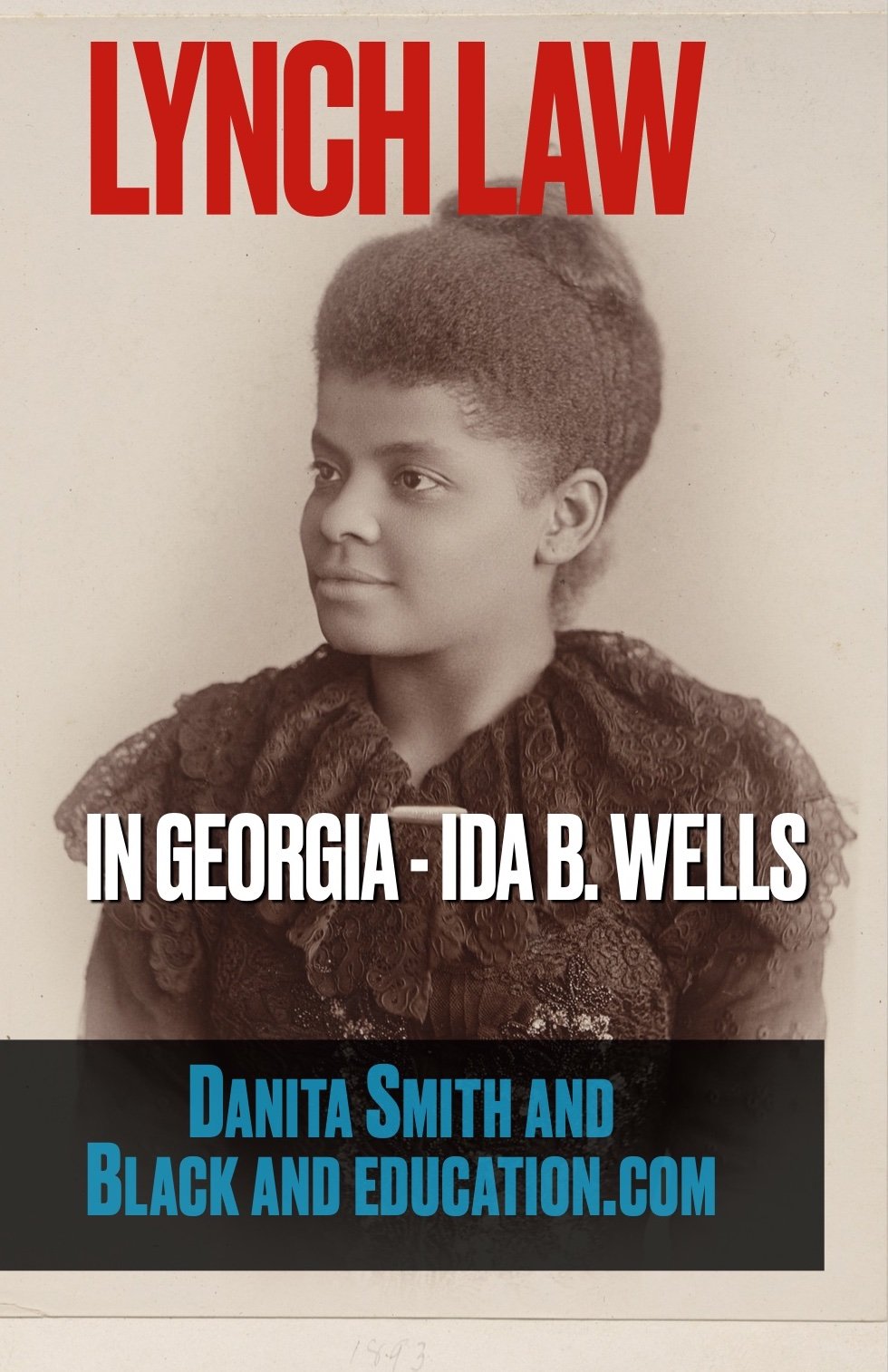

Lynch Law in Georgia by Ida B. Wells

Read an excerpt below. Purchase entire ebook HERE.

Ida B. Wells wrote about several incidences in Georgia, in 1899. This is an excerpt of the murders of several men, who were tied together in a warehouse, awaiting trial the next morning on the accusation of arson.

“That the awful story of their slaughter may not be considered overdrawn, the following description is taken from the columns of the Atlanta Journal, as it was written by Royal Daniel, a staff correspondent. The story of the lynching thus told is as follows :

“Palmetto, Ga., March 16.—A mob of more than 100 desperate men, armed with Winchesters and shotguns and pistols and wearing masks, rode into Palmetto at 1 o’clock this morning and shot to death four Negro prisoners, desperately wounded another and with deliberate aim fired at four others, wounding two, believing the entire nine had been killed.

It was just past the hour of midnight. The guards were sleepy and tired of the weary watch and the little city of Palmetto was sound asleep, with nothing to disturb the midnight hour or to interrupt the crime that was about to be committed.

Without the slightest noise the mob of lynchers approached the door to the warehouse. Not a false step was made, not a dead leaf was trod upon and not even the creaking of a shoe or the clearing of a throat broke the stillness.

With a noise that shook the buildings and threw every man to his feet the big fireproof door was suddenly struck as if with the force of a battering ram.

The guards sprang to their guns and the Negroes screamed for mercy.

But there were rifles, shotguns and pistols everywhere.

The little anteroom was packed full of armed men in an instant. The men seemed to come up through the floor and through the walls, so rapidly did they fill the room. And still others poured in at the door, and when the room was filled so that not another man could enter, the door was slammed to with awful noise and force.

The Negroes were screaming at the top of their voices.

“Hands up and don’t move; if you move a foot or turn your hands I will blow your damned brains out,” came the stern and rigid command from a man of small, thick stature, his face wholly concealed by a mask of white cloth and holding in his hands a couple of dangerous horse pistols.

The guards threw their hands up above their heads, all except one guard, James Hendricks, who lifted only one hand, while the other firmly grasped his revolver.

“I’ll blow hell out of you in a minute if you don’t put that hand up,” came the warning, and the hand followed the other one.

The command was then given to move, and move quick.

“You guards, move, and move quick, if you don’t want to get your brains blown out,” cried the low man, who was the mob’s leader.

The guards were then placed in line, six of them, and marched around the room and then marched to the front of the room, near the door through which the mob had entered.

They were placed in line against the front wall of the building and ordered not to move at the cost of their lives.

They did not speak, neither did they move, and not a word was said by the guard to the mob.

The men then walked around where they could get a good look at the trembling, pleading, terror-stricken Negroes, begging for life and declaring that they were innocent.

There was a moment’s pause of deliberation. The Negroes thought it meant that the assassins hesitated in their bloody deed, but the men hesitated only because they wanted deliberate action and a clear range for their bullets.

The Negroes, helpless, tied together with ropes, begged for mercy, for they saw the cold gun barrels, the angry and determined faces of the men, and they knew it meant death—instant death to them.

"Oh, God, have mercy!” cried one of the men in his agony. “Oh, give me a minute to live.”

The cry for mercy and the prayer for life brought an oath from the leader and derisive laughter from the mob.

“Stand up in a line,” said the man in command. “Stand up and we will see if we can’t kill you out; if we can’t, we’ll turn out.”

The Negroes faltered.

“Burn the devils,” came a suggestion from the crowd. “No, we’ll shoot ’em like dogs,” said the mob’s leader. “Stand up, every one of you and get up quick and march to the end of the room.”

The Negroes slowly stood up. The mob came closer and pressed about the stacks of furniture that had been stored in the room.

The leader asked if everybody’s gun was loaded and the men answered in the affirmative.

The Negroes pleaded and prayed for mercy.

They stood, trembling wretches, jerking at the long ropes that held them by the waist and about the wrists.

“Oh, give me a minute longer!” implored Bud Cotton.

“My men, are you ready?” asked the captain, still cool and composed and fearfully determined to execute the bloodiest deed that has ever stained Campbell County.

"Ready,” came the unanimous response.

“One, two, three—fire!” was the command, given orderly, but hurriedly.

Every man in the room, and the number is estimated at from seventy-five to one hundred and fifty, fired point blank at the line of trembling and terror-stricken bound wretches.

The volley came as the fire from a gatling gun.

It filled the warehouse with smoke and flame and death and brought a wail of horror that chilled the helpless guard.

The volley awakened the peaceful town of Palmetto and from every house the excited citizens ran.

“Load and fire again,” shouted the captain of the mob, and his voice was heard above the screaming and death cries of the wounded and dead.

The men rapidly loaded their guns, then fired at the given command.

“Now, before you leave, load and get ready for trouble,” came the captain’s order, and then men loaded their guns and got ready to leave the bloody room.

The guard was not relieved, however, until every man had left the building and all was safe for their hasty flight.

“I wonder if they are all dead,” said one of the mob, when the order was given to leave the building.

“I reckon so,” said one of the mob.

“But we had better see,” said the captain coolly and assuming an air of business.

A detail of probably a half dozen men, probably a dozen and maybe more, the guard does not remember just how many, was sent forward into the blood and brains and into the twisting mass of dying men to examine if all were dead. They were given orders to finish those who were not dead.

The detail rushed forward.

The men jerked the fallen, twisting and writhing and bleeding bodies about.

The first man they reached was not dead. He was still groaning, and the breath was coming in great, quick gasps.

A pistol was placed at his breast and every chamber was emptied.

“He’s dead now,” laughed one of the crowd.

Other men, wounded, bleeding, moaning and begging, were caught, turned over and pistols emptied into their bodies.

But the shooting had made so much noise that the mob concluded its safety lay in flight.

The Negroes were quickly examined and with a parting shot and a volley of oaths of warning the mob left the warehouse and rushed to their horses.

The men ran from the warehouse to the little spot in the center of the town, where horses are tied by countrymen and merchants.

They mounted quickly and began their ride for life.

With a sweeping of falling and echoing hoofs the cavalrymen dashed down the principal street at breakneck speed.

Mr. Henry Beckman, who lives a few hundred yards beyond the scene of the murders, heard the firing and ran from his house to the railroad tracks.

The horsemen, using the lash and urging their horses to their highest speed, dashed into view.

“Hello,” said Beckman, “what does all that firing mean?”

Beckman was answered with an oath and told to get into his hole as quickly as possible. “If you don’t, we’ll kill you on the spot,” was the warning.

Beckman flew for life, ran through the yard and entered the house as quickly as possible.

Dr. Hal L. Johnson saw a crowd of men on foot running down the sidewalk.

He hailed them, but there was no response.

“There must have been more than one hundred men on horses,” said Mr. Beckman this morning, in telling the Journal of his wild night experience with the mob.

When the mob left, the guards, who had been held against the warehouse wall at the points of guns and pistols, turned their faces toward the scene of carnage and death.

The furniture in the room had been splintered and wrecked with bullets and the contortions of the Negroes.

On the floor, near the center of the room, were two Negroes, still tied with the rope, locked in each other’s embrace. Near their bodies streams of blood were dyeing red the floor and spreading out in pools.

Just beyond were two more bodies. These Negroes were dead, too.

Near the fireplace was John Bigby, twisting and writhing in his agony. Blood was spouting from a number of wounds.

Under the beds and tables and piles of furniture were other bodies, every prisoner apparently dead, except Bigby, who was fast regaining consciousness.

The guards opened the door cautiously, but there was no sign of the mob, save the echoing footfalls on the country road.”

Wells-Barnett, Ida B., Lynch Law in Georgia, (Chicago, 1899).